For the last couple of years (since July 2018), I’ve been receiving “sextortion” emails. There a few variations, but the basic gist is always the same:

“I’ve hacked your webcam and filmed you masturbating, now pay me money or I’ll send the video to everyone you know.”

They often include my password, in an attempt to prove that they’ve got access to my computer.

The ransom amount also varies, but they always ask for it to be paid in Bitcoin. The cheapest was €500, and the most expensive was $7,000.

First things first: this is an empty threat. I’ve received thousands of these emails, but I’ve never replied to the sender or paid any money, and there have been zero consequences. In fact, I don’t believe that the alleged video or malware actually exists at all. However, there are a few things you can do to protect yourself.

Passwords

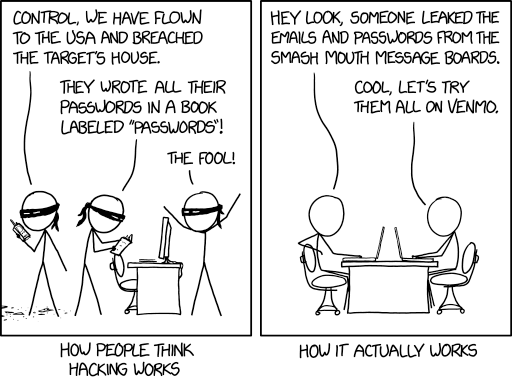

Let’s start with the password. If they didn’t install any malware, how do they know it? The most likely explanation is that it came from an existing data breach. You see these in the news every so often: website X has been hacked, and now all the account details have been leaked. For instance, LinkedIn had a data breach in 2012, which exposed the passwords for 117 million accounts.

Chances are, the people who send these emails aren’t the same people who actually hacked into the website. Instead, they’re just doing a mail merge: they’ve got a standard template, and a list of accounts (email address + password), then they’re sending the same message to everyone on that list. Sometimes they get it wrong, because they’re too incompetent to actually use their software properly. For instance, I’ve received messages like this:

“It appears that, (), ‘s your password.”

Obviously my password was supposed to go between the brackets, but they missed it out. Similarly, suppose that my password was “frogger”. I’ve seen some emails that claim it’s “frogge” and others that claim it’s “rogger” (i.e. they’ve missed out the first/last character). These people are not the elite hackers that they claim to be!

Related to that, the emails I’ve received are deliberately vague about which password they’ve got; they’re relying on the fact that a lot of people re-use passwords between websites. If they said “We know your Tesco password”, that’s annoying, but it’s not too bad. However, if I’ve also used that password for Gmail, it sounds more plausible that they could get access to all of my contacts.

Similarly, some of the extortion emails refer to porn sites, but they don’t mention which one. Here are some sample quotes:

“I actually setup a software on the X video clips (sexually graphic) site and you know what, you visited this web site to experience fun (you know what I mean).”

“I put in place a viruses over the adult videos (porno) web-site and you know what, you visited this website to have fun (you know very well what I mean)”

“the video you were viewing (you have a good taste lol)”

“I am in great shock of your fantasies! I’ve never noticed something like this!”

By contrast, they’re not saying “I know that you visited WetRiffs.com.” They’re just relying on your guilty conscience to fill in the blanks based on vague hints. (This is similar to the cold reading technique that fake mediums use, e.g. “I sense that you have lost an elderly relative.”)

Ideally, a company would inform you when they suffer a breach; typically, they would also force you to change your password the next time you log in. However, that might not always happen, e.g. if a company goes out of business and their computers are disposed of without wiping the hard drives properly. In that situation, there’s nobody left to send out a notification.

So, what steps can you take?

- Use a password manager. I personally use KeePass, but there are others out there.

- If you receive one of these extortion emails, and you’re still using the password that it mentions, change that password.

- Use a unique password for every app/website.

- Use strong passwords where possible, particularly if you don’t have to type them in manually.

- Don’t repeat security questions between sites; ideally, don’t give them real answers.

- Go to Troy Hunt’s site: Have I Been Pwned. You can enter your email address, then it will tell you if your account details have been included in any data breaches. Make sure that you’ve changed your password since the breach occurred. You can also subscribe to notifications, so that you’ll get a message if any new breaches include you.

Bear in mind that the people who send these emails aren’t the only threat; other people will work more quietly, by trying out the credentials from a data breach on various other websites.

I know people who have lost control of their Facebook account, where someone else hijacked it and used it to post spam (e.g. adverts for sunglasses). That could happen if you used the same password for Facebook and Adobe, then Adobe got breached.

Another issue is that you might not know which site actually got hacked. If the emails mention a password that you only used in one place then you know it came from there. If you used the same password for 20 different websites then it could have been any of them, and that means you need to change your password on all of them. (If you do know the specific website, and they haven’t notified you, please notify them.)

Some websites use security questions (in case you forget your password), e.g. “what was the name of your first pet?” If you’ve answered the same question on multiple websites, then one website gets breached, an attacker could use your answer to impersonate you on another site (even if you used unique passwords). This could even be used for identity theft, e.g. taking out a new credit card in your name. So, I supply fake answers to these questions, and store them in my password manager.

Aside from breaches, there’s also a risk that someone could guess your password. It’s unlikely that they’ll do a brute force approach, testing possible passwords like “aFCjxS5HENefm9wFyFSF”, because that would take ages. It’s far more efficient to use a word list that contains common passwords from previous data breaches. For instance, when RockYou had a data breach in 2009, that revealed the passwords for 32.6 million accounts. The same 13 passwords were used across 5% of those accounts (1.6 million). So, if your password is “qwerty” or “abc123”, an attacker will guess it instantly. I mentioned KeePass: this will generate random passwords for me, then I can copy/paste them into websites.

Webcams

As I said above, these extortion emails are a hoax: they don’t actually have any video of you. However, is it possible that another attacker could turn on your webcam remotely? Yes.

Zoom is quite popular at the moment (due to the COVID-19 pandemic), where people are working from home and using it for video conferences. However, they had a security problem in 2019, combining 2 issues:

- If you installed the Zoom client, then uninstalled it, it kept a web server running on your machine that would silently re-install the software if you went to a website that required it. Apparently this was intended to make life easier, to make the experience seamless rather than bothering the user with questions like “Do you actually want to use this software again?”

- If you went to a malicious website, it could use the Zoom client to join you to a meeting and turn on your webcam, without you even knowing about it.

That particular issue only affected Apple Macs, but it’s plausible that there could be a similar issue affecting other platforms (e.g. a Windows PC).

Aside from video conferencing software, suppose that you have a general vulnerability on your computer, e.g. if you haven’t installed the latest “patch Tuesday” security updates for Windows. An attacker could then exploit the vulnerability to get into your computer. As a penetration tester, I’ve used the Meterpreter shell, which contains built-in commands to turn the webcam and microphone on and off.

So yes, if you have a webcam on your computer (which most laptops do) it is entirely possible that an attacker could turn it on and record what you’re doing.

That said, you need to consider what the webcam would actually see. If you’ve actually done a video chat with anyone, you’ll already know the answer: it will typically show your head and shoulders, but nothing below the waist. So, even if you were masturbating in front of your computer, the webcam probably wouldn’t record that. It’s more plausible that it could get naked pictures of you, e.g. if you walk past the computer after you’ve got out of the shower.

Knowing this, what you can do about it? There are typically 4 ways to manage risk:

- Transfer

- Avoid

- Mitigate

- Accept

Transferring risk typically means outsourcing it. For instance, if a shop uses PayPal rather than taking credit card payments directly, it becomes PayPal’s job to protect the credit card details. However, that’s not really applicable in this context. You might be able to take out some kind of insurance policy, e.g. if you’re a celebrity and nude photos would be worth a lot of money, but again that won’t apply to most people.

Avoiding the risk is a bit more plausible. To quote a line from Hitch: “You cannot use what you do not have!” More specifically, if you don’t have a webcam then an attacker can’t use it to film you.

Risk is the combination of the likelihood and the impact. So, mitigating the risk means that you reduce one/both of those factors. In this context, there’s not much you can do about the impact, but you can reduce the likelihood. Security people talk about controls: physical, logical, and management. In this case, I recommend a physical control, for a low tech solution. You might be able to buy a lens cap that would fit over the end of your webcam, or you could simply drape a sock over it when it’s not in use. (A logical control would mean configuring your software, but that could be bypassed by malware. A management control would mean changing your behaviour, e.g. making sure that you’re fully dressed when you go near the computer.)

The final option is to accept the risk. For instance, you might say “I’m not doing anything wrong, and if people spy on me then I have nothing to be ashamed of; that reflects on them, not on me.” You could combine this approach with mitigation, e.g. that you drape a sock over the webcam to reduce the likelihood, but if you forget to put it back after a video call then you can live with the impact.

Conclusion

Just to recap the key points, you don’t need to worry about any extortion demands you receive, so you can simply delete those emails. However, you should look at how you manage your passwords and your webcam, as a general precaution against other attacks.

Leave a Reply